Cause and effect can play out in unexpected ways. That serendipity is the subject of an Edo-period proverb: A gale blows, bucket makers prosper. Here is the logic of the tale.

Dust rises when the gale blows.

The dust blows into people’s eyes, robbing some of their sight.

Demand for samisen (three-stringed musical instruments) increases (playing the samisen having traditionally been a vocation for the blind).

Samisen makers kill more cats for their skins.

Mice multiply as the cat population dwindles.

The mice gnaw on buckets.

Bucket makers prosper as demand for their product swells.

Akechi Mitsuhide (1528–1582). The name is synonymous in Japan with the act of betrayal. The historical reality, as usual, is more complex than the caricatures that have shaped our perceptions. Of primary interest here, however, is not so much the reality of the history as the happenstance of the pottery-related events.

The warlord Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) was the first person to bring all of Japan under more or less unified leadership. Mitsuhide had served Nobunaga as a worthy general and vassal, but something gnawed at his loyalty. Whatever his reasons (a subject of continuing debate among historians), Mitsuhide turned on his liege lord in 1582. He led a force of 13,000 warriors against Nobunaga while the latter was encamped at the Kyoto temple of Hon-no-ji. Mitsuhide’s force set fire to the temple, and Nobunaga died at his own hand or in the fighting amid the flames. Alas, forces led by another of Nobunaga’s generals, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), routed Akechi’s force just days later, and someone of uncertain identity killed Akechi as he fled.

Nobunaga had been a great lover of cha-no-yu (tea ceremony) and of tea ceramics. Among the tea masters that he employed was Sen no Rikyu (1522–1591), renowned today for having refined the wabi-sabi understated elegance of cha-no-yu. After the death of Nobunaga, Hideyoshi took control of Japan, and he employed Rikyu as a tea master. That relationship frayed, however, and Rikyu ended up taking his own life under pressure from Hideyoshi.

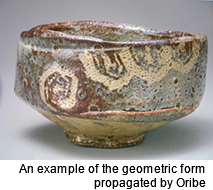

Rikyu’s successor as a tea master under Hideyoshi was his disciple Furuta Oribe (1544–1615). Oribe (oh-ree-bay) exerted a powerful and lasting influence on Japanese ceramics, especially in regard to items used in the tea ceremony and most notably in regard to their geometric form. He perfected the pottery aesthetic that Rikyu had initiated in commissioning chawan tea bowls from Raku (Tanaka) Chojiro (died 1592).

Chojiro was the progenitor of the Raku line of potters. Under Rikyu’s guidance, he broke with the tradition of geometrical symmetry in tea vessels and created works of distinctive asymmetry. Oribe furthered that departure in overseeing, as Hideyoshi’s tea master, a sea change in Japanese pottery. Under Oribe’s supervision, a highly sophisticated asymmetrical geometry took hold in every principal genre of Japanese pottery, including Raku, Shino, Karatsu, Hagi, Bizen, Shigaraki, Iga, and the Mino ware that would become known as Oribe.

Oribe’s hegemony over Japanese pottery aesthetics began during an era that we know as Azuchi-Momoyama. We can regard that period as beginning with Nobunaga taking control of Kyoto in 1568 and ending with Hideoyoshi’s successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), taking control of Japan in 1600 and moving the nation’s political capital to Edo (Tokyo) three years later.

The name “Azuchi-Momoyama” refers to Nobunaga’s castle in the Azuchi district of what is now Shiga Prefecture and to Hideyoshi’s castle in the Momoyama (Fushimi) district of Kyoto, though we commonly abbreviate it as just “Momoyama.” And “Momoyama pottery”—chawan tea bowls, mizusashi water jars, and other tea pottery of the style favored during the Momoyama period—became an enduring benchmark for sublime geometry in ceramics.

Numerous masterworks of Momoyama pottery originally owned by daimyo warlords passed into the hands of business tycoons, high government officials, and other collectors of means in the modern era. Prominent potters of successive eras also became preoccupied with the aesthetic principles embodied in Momoyama pottery, and their “Neo-Momoyama” work earned a devoted following among collectors and dealers.Momoyama and Momoyama-inspired work, mainly for the tea ceremony, and selected work from China and from the Korean peninsula became the chief dynamics in the growth of Japan’s market for high-end ceramics.

In the 20th century, the mingei (folk art) movement arose under the leadership of Yanagi Soetsu (1889–1961). The mingei movement was partly a rejection by Soetsu and his kindred spirits of the elitism that they perceived in Japan’s high-end pottery market. It was also an effort to preserve the pottery traditions that they discovered and valued in the countryside of Japan and its then-colony Korea. Ironically, works by the best-known mingei potters, such as Kawai Kanjiro (1890–1966), Hamada Shoji (1894–1978), and Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886–1963), attained high prices, and mingei secured a place in the elitist pottery market that its perpetrators had rejected.

We also witness a rejection of the pottery market’s norms in the mid-20th-century emergence and subsequent growth of nonfunctional, abstract pottery. Abstract works by such potters as Yagi Kazuo (1918–1979) and Akiyama Yo (born 1953) have also secured a solid and pricy position in Japan’s pottery market.

So what goes around comes around. Christianity arises as the fulfillment of elements implicit but unorchestrated in Judaism, just as Zen will later do vis-à-vis traditional Buddhism. Punk rock arises as an alternative to what its proponents perceive as the overly saccharine tendencies of mainstream rock. No sooner has it taken shape as “counterculture” than it assumes a place in mainstream culture.

To work in the sphere of pottery in Japan is to become subject to categorization, be it “tea ware,” “mingei,” “abstract,” or whatever. Some benighted potters who chaff at such categorization strive to position themselves beyond labels, but their pathetic efforts merely serve in the end to underline the inevitability of characterization in reference to categories.

Which brings us back to Akechi Mitsuhide and to the happenstance of cause and effect. Had Mitsuhide not turned ill-advisedly on Nobunaga, he would have continued to serve as his liege lord’s tea master. Had he lived into the 17th century, the aesthetic propagated by Furuta Oribe presumably would not have taken hold, and the Momoyama revolution in geometric form would not have outlived Rikyu and Chojiro and their immediate circle.

Oribe, incidently, shared the fate of Rikyu. He got on the wrong side of Ieyasu, which obliged him to take his own life, and the tea ceremony and Oribe-inspired pottery atrophied soon after his death.

We can only speculate as to how pottery would have evolved had Oribe not run afoul of Ieyasu, He was 71 when he died, so he wouldn’t have lived a whole lot longer. Tempting nonetheless is the thought that a somewhat longer-lived Oribe might have steered pottery to some sort of uber-Oribeism. The thought also occurs, however, that things might have turned out otherwise: that pottery aesthetics might have succumbed to a numbing inertia born of ubiquity.

Grateful for the pottery traditions that we have inherited, we can but marvel at the serendipity that they have traversed. A gale blows, bucket makers prosper.

How to Convey Really, Really Bad News

Jervas,the steward of a bank owner, calls on the son of his master to report some untoward tidings.

- Son:

- Ha! Jervas, how are you, old boy? How do things go on at home?

- Jervas:

- Bad enough, your honour; the magpie’s dead.

- Son:

- Poor Mag! So he’s gone. How came he to die?

- Jervas:

- Overeat himself, sir.

- Son:

- Did he? A greedy dog; why, what did he get he liked so well?

- Jervas:

- Horseflesh, sir; he died of eating horseflesh.

- Son:

- How came he to get so much horseflesh?

- Jervas:

- All your father’s horses, sir.

- Son:

- What! Are they dead, too?

- Jervas:

- Aye, sir; they died of overwork.

- Son:

- And why were they overworked, pray?

- Jervas:

- To carry water, sir.

- Son:

- To carry water! And what were they carrying water for?

- Jervas:

- Sure, sir, to put out the fire.

- Son:

- Fire! What fire?

- Jervas:

- Oh, sir, your father’s house is burned to the ground.

- Son:

- My father’s house burned down! And how came it to set on fire?

- Jervas:

- I think, sir, it must have been the torches.

- Son:

- Torches! What torches?

- Jervas:

- At your mother’s funeral.

- Son:

- My mother dead!

- Jervas:

- Ah, poor lady! She never looked up, after it.

- Son:

- After what?

- Jervas:

- The loss of your father.

- Son:

- My father gone, too?

- Jervas:

- Yes, poor gentleman! He took to his bed as soon as he heard of it.

- Son:

- Heard of what?

- Jervas:

- The bad news, sir, and please your honour.

- Son:

- What! More miseries! More bad news!

- Jervas:

- Yes sir; your bank has failed, and your credit is lost, and you are not worth a shilling in the world. I make bold, sir, to wait on you about it, for I thought you would like to hear the news.